The Record

Con Brio: Conductor Gisèle Ben-Dor blazes a rare path in her life and work

By Ryan Jones

Her father was an accountant, and so Gisèle Ben-Dor assumed she would be an accountant, too. If you were a teenage girl growing up in Uruguay three decades ago, this was how things worked. Careers paths weren’t chosen so much as they were inherited.

Always more suited to Tchaikovsky than taxes, Ben-Dor never did get that economics degree. She became, instead, a musician and a conductor. She lives in the United States now, very much a woman of her time and environment, and she is certain her own children will feel no pressure to follow their mother’s line of work.

Good thing, too. They don’t appear to be interested.

“When my oldest son was about 3 years old, someone asked him, ‘So, you want to be a conductor when you grow up?'” Ben-Dor recalls. “He said, ‘No. That’s for girls.'”

She follows the punch line with a joyful laugh, but there is a point to this anecdote, and Ben-Dor makes sure it is not missed.

“You see? That’s the nature of prejudice. This is what he knows,” she explains. “How can a conductor possibly be a man? He can’t identify with that.”

Her oldest son, Roy, is 16 now, no doubt old enough to understand that the job of leading symphony orchestras is not just for girls, and that his mother is something of a rarity. The musical director for two American orchestras, a sought-after guest conductor, and an acclaimed recording artist, Ben-Dor has fought the archaic tendencies of the classical music world, earning a reputation and a fan base that seem to grow daily.

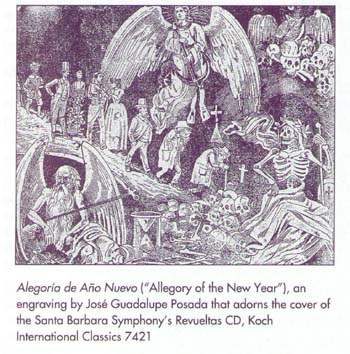

Settled in Englewood Cliffs, where she lives on a quiet street with her husband Eli and sons Roy and 7-year old Gabriel, Ben-Dor has a home base from which her far-reaching career is maintained. Currently, she stands at the helm of the Santa Barbara (Calif.) Symphony and the Boston Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra, and appears regularly with orchestras from around the world.

“I’ve been commuting for seven years,” she says with a grin, “and I’m sick of it.”

Travel, it seems, is in her blood.

Sensing the growing tension in pre-World War II Europe, Ben-Dor’s parents left Poland in the early 1930s and settled in Uruguay. Growing up in the small South American nation, she learned half of the six languages she now speaks and developed an intense love of music. “Obsessed,” she says. “That would be the word.

“When I was 3 years old, I asked my parents to buy me a piano, so they bought me one for my fourth birthday,” she continues. “It was just the greatest joy I could’ve had. I would spend hours there. By the time I was 5, I could play anything.

By 12, she was the musical director at her school, and by 14, she was being paid to conduct. She left Uruguay at 18, following her family roots to Israel, where her musical studies intensified and she eventually married. Seven years later, she arrived in the United States, attending a two-year graduate program at Yale and preparing to jump-start a late-blooming career.

Ben-Dor went back to Tel Aviv for her conducting debut, nine months pregnant with Roy. The young family lived briefly in Dumont, until a job as an assistant conductor in Louisville began a series of moves – first to Kentucky, then to Houston, and finally back to New Jersey. Settled in Bergen County, where Eli worked, Ben-Dor took over the Annapolis Symphony, then accepted jobs in Boston and Santa Barbara.

“If I could find an orchestra within a two-hour drive of here, I would be so happy,” she says. “New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, anywhere.”

She has made her presence felt locally, guesting with the New York Philharmonic on occasion, including a recent appearance during which she stepped in without rehearsal and led the orchestra through a Beethoven overture and a Mahler symphony.

Because of performances like that, and because of the emotional depth of her recorded work – on her most recent, she leads the London Symphony Orchestra through the Alberto Ginastera ballets “Panambi” and “Estancia,” just released on BMG/Conifer – Ben-Dor has been inundated with glowing reviews.

“Critics, there are those who will adore you,” she says, “and those for whome you can do no good.”

The statement applies to any artistic medium, but it carries an extra sting for Ben-Dor, a woman in a decidedly patriarchal field. For all the critics who have raved about her, she remembers those who refused to mention her name. For all the musicians who have praised her ability to bring out the best in them, she remembers those who wouldn’t look her in the eyes.

She remembers them, but she also knows they are in the minority. Mostly, there is acceptance, even appreciation for Ben-Dor’s talent, intelligence, and artistic insight. “There is room for women, but it takes time for some people to realize that,” she says. “It’s not easy. You have to prove it. I realize how long it takes.”

It shouldn’t take too long. Her son had it figured out by the time he was 3 years old.

Much of Revueltas’s music has the kind of brash, rhythmically propulsive character commonly associated with Latin-American culture. But a much more introspective style can also be heard in his music, as it can be in the music of Ginastera (1916-83), an Argentinean who was influenced not only by the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla but by Stravinsky, Bartok, and the French Impressionists. Ginastera’s music had three clear periods. The early ballets Panambi, based on a Guarani Indian legend of love and magic, and Estancia (“The Ranch”), could be termed “objective nationalism.” Estancia ends with a fiery malambo, the typical dance of the gauchos, but also has many lyrical moments reflecting life on the Argentinean Pampa. I’ve seen these vast grasslands and traveled through them. It’s a lonely existence, and this comes out in the words of Martin Fierro, Jose Hernandez’s epic poem of 1873-which we had to memorize as students, and which Ginastera uses in parts of Estancia. When I conducted the complete ballet with the Santa Barbara Symphony in 1997 the narration and singing were in Spanish. I would always want the singer/narrator to be an Argentinean or Uruguayan (or pretend to be one, just as singers perfect their diction in Italian, French, German, Viennese dialects, etc.). I couldn’t hear it any other way.

Much of Revueltas’s music has the kind of brash, rhythmically propulsive character commonly associated with Latin-American culture. But a much more introspective style can also be heard in his music, as it can be in the music of Ginastera (1916-83), an Argentinean who was influenced not only by the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla but by Stravinsky, Bartok, and the French Impressionists. Ginastera’s music had three clear periods. The early ballets Panambi, based on a Guarani Indian legend of love and magic, and Estancia (“The Ranch”), could be termed “objective nationalism.” Estancia ends with a fiery malambo, the typical dance of the gauchos, but also has many lyrical moments reflecting life on the Argentinean Pampa. I’ve seen these vast grasslands and traveled through them. It’s a lonely existence, and this comes out in the words of Martin Fierro, Jose Hernandez’s epic poem of 1873-which we had to memorize as students, and which Ginastera uses in parts of Estancia. When I conducted the complete ballet with the Santa Barbara Symphony in 1997 the narration and singing were in Spanish. I would always want the singer/narrator to be an Argentinean or Uruguayan (or pretend to be one, just as singers perfect their diction in Italian, French, German, Viennese dialects, etc.). I couldn’t hear it any other way.