A Taste of Latin Discoveries Down South

By Gisèle Ben-Dor

As music director of the Santa Barbara Symphony I’m constantly commissioning new works from composers who were born in the United States or who live and work here. I’m an American citizen who’s been here for 20 years, and my two sons are growing up here. But I also began promoting the cause of Latin American composers many years ago, realizing that I could usefully devote my resources with authority to a largely unexplored area that I feel very strongly about. And working in a city that’s about 50 percent Hispanic I have found my own background to be particularly relevant.

I was born to Polish parents, raised in Uruguay, and educated further in Israel so my own background is quite rich and cosmopolitan. But growing up in South America I was exposed to all kinds of Latin music-bossa nova, samba, carnavalitos from the Andes, Argentina, Uruguay. The tango, the malambo. Caribbean music with its cha-cha-chas and merengues and salsas.I’m a classically trained pianist and self-taught guitarist who learned the folk music of Latin America by hearing it and playing it and singing it in my Spanish mother tongue as well as in Brazilian Portuguese.And I’m drawn to composers who borrowed from this music, just as Dvorak, Sibelius, and Smetana did with the folk music of their countries. I’m also trying to give symphony audiences music they haven’t heard before-by programming composers such as Mexico’s Silvestre Revueltas, Argentina’s Alberto Ginastera and Astor Piazzolla, and Brazil’s Heitor Villa-Lobos.

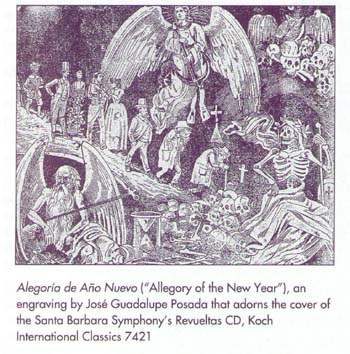

Revueltas, born on the last day of 1899, was the subject of a centennial tribute by the Santa Barbara Symphony in January of this year. Our four-day festival included the chamber orchestra version of Sensemaya and a large number of other orchestral and chamber works by Revueltas, some of them U .S. premieres; an exhibition of manuscripts, photos and scores; lectures by Roberto Kolb-Neuhaus, a Revueltas scholar from the University of Mexico; a family concert with bilingual narration in a mostly Mexican neighborhood, where the orchestra was joined by the Mexican EspiraI puppet theater and a wonderful Mexican percussion ensemble called Tambuco; a screening of three of the ten films for which Revueltas scored music; and the U .S. premiere of the magnificent Symphony No.10 (” Amerindia”) by Villa-Lobos, one of several Latin composers I included in the festival to give context to the music of Revueltas. We were able to take a nucleus of existing activity-subscription and family concerts, pre-concert activities, past performances of Revueltas’s music-and add chamber music, film screenings, and an exhibition. exhausting as it was, I would gladly do it all over again.

The films were made in the 1930s but are still in good condition. We had English subtitles prepared, and I chose to screen one of the films, Redes (“Nets”), with live accompaniment by the orchestra. Redes is a tragic story about poor fishermen in turn-of-the-century Mexico who try to form a union. It has a very visceral impact, with beautiful camera work by Paul Strand and strong music that evokes images from the fishing village, such as the rowing of the boats. The film works extremely well with live accompaniment, because there’s almost no overlap between the dialogue and the music. (This is not the case with Vamonos Con Pancho Villa and La noche de los Mayas, which we screened without live accompaniment to give a taste of Revueltas’s other film music.) All but about ten bars of the music from Redes was removed from the soundtrack, and we used a score that I put together from the published suite and additional music that’s heard in the original film. So now Redes could be done with live accompaniment by any orchestra.

The Santa Barbara audience’s first taste of Revueltas had come in the 1997-98 season with Sensemaya. For the 1998-99 season-a year before our Revueltas festival-I had the orchestra accompany the Santa Barbara State Street Ballet in La Coronela, which tells the story of oppression and liberation in Mexico in the early years of this century. The music was completed by others after Revueltas’s death, but the score used in the 1940 premiere disappeared and had to be reconstructed by conductor Jose Limantour and composer Eduardo Hernandez Moncada. Our performance (which also included Revueltas’s Itinerarias and was subsequently recorded) was the first time the reconstructed ballet had been done since its premiere in 1942. I followed up La Coronela with La Noche de las Mayas. These four works helped prepare our audience for the Revueltas festival the following season.

In the book “Silvestre Revueltas por el mismo” (best translated as “Silvestre Revueltas, in his own words) I discovered an extraordinary personality, deeply touching both in its radiant, life-embracing moments and in its melancholy and despair. At the time of his early death (at 41) he was still writing music with a very strong Mexican influence. Ken Smith writes in his notes for our recording of La Coronela that “for Revueltas, whose teenage years were spent in the throes of the Mexican Revolution, music was about establishing national identity. . .Shutting the door on the old cultural models was, by extension, a rejection of colonial society; his musical ‘vulgarity’ an embrace of the people.” La Coronela begins with a musical depiction of upper-crust Mexican society around 1900. In the middle of the story we have La Coronela-The Lady Colonel, like the woman with the torch in the French Revolution and the ballet ends with battle music, a long elegy for Los Caidos (The Fallen), and a jubilant salute to Los Liberados (The Liberated).

Much of Revueltas’s music has the kind of brash, rhythmically propulsive character commonly associated with Latin-American culture. But a much more introspective style can also be heard in his music, as it can be in the music of Ginastera (1916-83), an Argentinean who was influenced not only by the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla but by Stravinsky, Bartok, and the French Impressionists. Ginastera’s music had three clear periods. The early ballets Panambi, based on a Guarani Indian legend of love and magic, and Estancia (“The Ranch”), could be termed “objective nationalism.” Estancia ends with a fiery malambo, the typical dance of the gauchos, but also has many lyrical moments reflecting life on the Argentinean Pampa. I’ve seen these vast grasslands and traveled through them. It’s a lonely existence, and this comes out in the words of Martin Fierro, Jose Hernandez’s epic poem of 1873-which we had to memorize as students, and which Ginastera uses in parts of Estancia. When I conducted the complete ballet with the Santa Barbara Symphony in 1997 the narration and singing were in Spanish. I would always want the singer/narrator to be an Argentinean or Uruguayan (or pretend to be one, just as singers perfect their diction in Italian, French, German, Viennese dialects, etc.). I couldn’t hear it any other way.

Much of Revueltas’s music has the kind of brash, rhythmically propulsive character commonly associated with Latin-American culture. But a much more introspective style can also be heard in his music, as it can be in the music of Ginastera (1916-83), an Argentinean who was influenced not only by the Spanish composer Manuel de Falla but by Stravinsky, Bartok, and the French Impressionists. Ginastera’s music had three clear periods. The early ballets Panambi, based on a Guarani Indian legend of love and magic, and Estancia (“The Ranch”), could be termed “objective nationalism.” Estancia ends with a fiery malambo, the typical dance of the gauchos, but also has many lyrical moments reflecting life on the Argentinean Pampa. I’ve seen these vast grasslands and traveled through them. It’s a lonely existence, and this comes out in the words of Martin Fierro, Jose Hernandez’s epic poem of 1873-which we had to memorize as students, and which Ginastera uses in parts of Estancia. When I conducted the complete ballet with the Santa Barbara Symphony in 1997 the narration and singing were in Spanish. I would always want the singer/narrator to be an Argentinean or Uruguayan (or pretend to be one, just as singers perfect their diction in Italian, French, German, Viennese dialects, etc.). I couldn’t hear it any other way.

In his middle period Ginastera uses language that’s more indirectly nationalistic, as in Bartok-inspired by, but not imitative of, folk music. Works include Glosses an Themes of Pablo Casals and Variaciones concertantes, which I included in my first Ginastera CD. And there’s the final period, which I’m working on now as I conduct and record his 1971 opera Beatrix Cenci in its European premiere in Geneva and his long-neglected Turbae ad Passionem Gregorianam in Madrid. Beatrix Cenci is dodecaphonic, aleatoric, ferociously expressionistic, experimental, and uncompromising, with no trace of folk music. It makes one think of multi-faceted artists like Copland (with whom Ginastera studied at Tanglewood) and Stravinsky and Picasso. Ultimately, Ginastera wanted to be seen as a universal musician, not solely as an Argentinean composer.

Wherever I conduct I try to do some music by Latin-American composers, but always alongside more standard repertoire. Rebellious and/ or original as some of them may have been, these composers fully belong in the cultural tradition of the West, no less than Mahler or Ravel. They learned their craft by being exposed to the great standard composers. In trying to bring out music that hasn’t been heard I hope audiences will understand this. The “third-world” countries of Latin America haven’t had the political muscle to push their culture in other countries-they’ve had so many other needs. I want to show that there is wonderful music here to be discovered.

It’s not a question of whether this music is as great as Beethoven or Brahms. We sometimes pay respect to European composers just because of one or two works that have found a place in the repertoire, and then we’re curious about anything else they may have written, no matter how mediocre. So I say quid pro quo: Listen to some of these Latin-American composers and you’re going to find treasures. Keep digging, just as you have done with the Europeans. I think we need to discover music that we didn’t know before – new music, even if it’s old.