American Record Guide

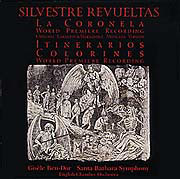

Silvestre Revueltas

Revueltas is the Mexican Prokofieff, though he’s sometimes compared to Stravinsky. Yet his music is brighter and more joyous than Stravinsky’s. Like Prokofieff, Revueltas simply cannot resist the temptation to burst into a good tune now and then, and he boasts a lively, irrepressible sense of humor. While his music can be stern, severe, and even quite radical by the standards of its time, it must always sing.

Revueltas is the Mexican Prokofieff, though he’s sometimes compared to Stravinsky. Yet his music is brighter and more joyous than Stravinsky’s. Like Prokofieff, Revueltas simply cannot resist the temptation to burst into a good tune now and then, and he boasts a lively, irrepressible sense of humor. While his music can be stern, severe, and even quite radical by the standards of its time, it must always sing.

Critic Tim Page argues that Revueltas’s fondness for percussion instruments suggests a kinship with Varese, though he admits that some of the music reminds him of Copland – “on mescal”, that is. Whether Revueltas experimented with hard drugs, I cannot say. Nonetheless, the addiction to alcohol that hastened his death in 1940 can be heard clearly in the angry, drunken outbursts that punctuate so many of his compositions. He shared Bartok’s fascination with folk music, though he did not feel the need to scour the countryside in search of native forms of expression. “Why”, he once wondered aloud, “should I put on boots and climb mountains for Mexican folklore, if I have the spirit of Mexico deep within me?” One also hears an Ivesian clash of popular and serious elements in his compositions, along with a hint of Respighi – as in the lush, luxurious opening bars of La Noche de los Mayas . Despite all these influences, Revueltas’s music is as vital and original as any composed in this century. For an excellent overview of the man, his music, and its many recordings, see Diederik De Jong’s review of Noche in March/April 1995.

… Revueltas began work on the ballet a Coronela (The Lady Colonel) shortly before he died in 1940. The story concerns the violent overthrow of a brutal, decadent dictatorship by the common folk. Alas, Koch’s sketchy booklet notes do not bother to tell us what role the Lady Colonel plays in this revolution or even which side she’s on. In any event, Revueltas had time to sketch only three of the ballet’s sour scenes. Shortly after his untimely death Blas Galindo completed the work, which was then orchestrated by Candelario Huizar. That version somehow vanished, along with all of the composer’s sketches. Nearly two decades later, conductor Jose Limantour decided to “reconstruct” the score. Just how he managed this feat without the sketches is also not explained in the notes. This time Eduardo Hernandez Moncada furnished the orchestration. Limantour – to whom we most certainly owe a debt of gratitude for compiling the enchanting suite from La Noche de Los Mayas – then selected items from two Revueltas film scores to replace the missing final scene. In addition, he spiced up Moncada’s orchestration. How much of the final product was actually written by Revueltas is open to question. Unless the original manuscript turns up, we’ll never know.

Whatever the case, the first three sections of the work lack the composer’s typical melodic inventiveness and colorful use of percussion. If Revueltas indeed wrote this music, his muse must have abandoned him after so many years of dissipation and mental instability. Except for the few numbers that have a recognizably Mexican flavor, this ponderous, busy, and uninspired score could have been written by Roussel – on an off day. The two film cues used in Scene IV leave the most lasting impression. ‘The Battle’ is appropriately horrific, with its exciting rhythms and vivid scoring, especially for the percussion. The composer had, after all, witnessed warfare first hand while fighting for the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War, and he knew quite well how to convey the chaos of the battlefield in musical terms. ‘The Fallen’ begins with a solemn trumpet melody followed by a touching episode for muted strings. After the trumpet intones ‘Taps’, the music becomes gentle and soothing. A powerful, dramatic peroration in the brass brings this memorable and touching scene to its conclusion.

The remaining works on Ms. Ben-Dor’s program, though brief, are fully authentic and vastly more compelling than this ersatz ballet. Indeed, you’ll find more interesting melodic ideas in either of these two short elections than in the entire ballet. Both are cast in simple three-part form, with a gentle, reflective central section surrounded by bustling, occasionally violent music. Itinerarios (Travel Diary) begins in the very bowels of the orchestra with the tuba, soon joined by the other low brasses and woodwinds. Several fascinating melodic fragments are introduced only to be quickly abandoned. Finally a series of dramatic fanfares leads to a strident, drunken climax. At 4:12 the mood changes abruptly as the soprano saxophone sings a transcendentally beautiful melody worthy of Hovhaness, though tinged with a hint of Gershwinesque melancholy. This eerie and beautiful interlude leads to a reprise of the agitated opening music, which is then cut off abruptly in typical Revueltas fashion.

Following a brief introduction by the percussion, Colorines erupts into an Ivesian orgy of dissonant counterpoint – though unlike Ives, the themes all have a Mexican flavor. After a short pause, the orgy resumes. Suddenly the noise and chaos end abruptly, and in its place we hear a gentle, mellifluous melody in the woodwinds. There’s a bit of Copland here, but the music also has an ancient quality. Finally, the percussive opening returns, another dissonant climax is built, and then the music screeches to a halt – as if cut off in mid-phrase.

Ben-Dor has an obvious affinity for this music, which she presents with great passion. Both orchestras play splendidly (the English Chamber Orchestra is heard only in Colorines ). The Santa Barbara ensemble boasts some very fine brass players and richer strings than one hears on the new Intersound Royal Philharmonic discs. Let us hope that these forces will soon bring us more Revueltas rarities – especially his neglected film scores.